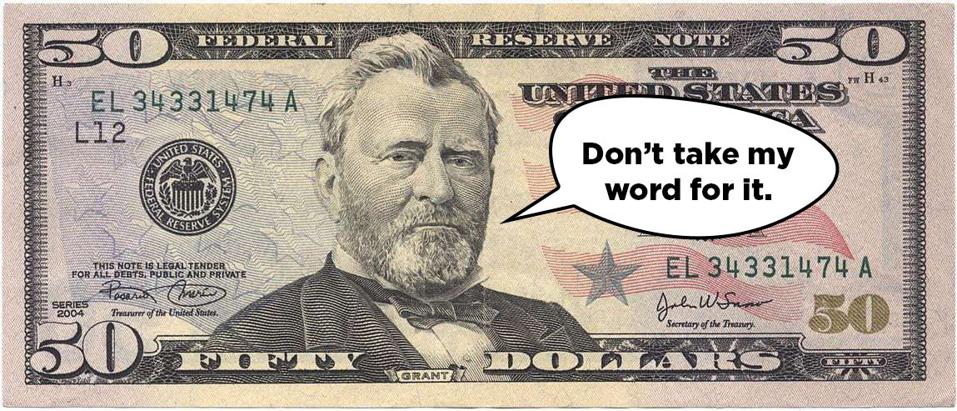

Let's talk about the phrase “take at face value” for a moment.

In dictionary terms, it means “to accept something as it appears, without looking for a hidden meaning.” The etymology goes back to the 1800s.

Taking something at "face value" was actually financial slang. It literally came from the value associated with the different faces on dollar bills: Ben Franklin's face was worth $100. Abe Lincoln was $5.

It was similar to the slang term “bucks,” which came from fur traders who used buckskins as currency.

I'm telling you this because I think this origin story is quite relevant to anyone who wants to be an innovative leader or problem solver today.

And that's for one very important reason.

It’s not true.

The truth is that the term “face value” does come from the 1800s, but it actually just referred to the front face of a stock document. This is much less of a fun origin story than the one about Presidential faces.

That little tidbit may not matter to you at all—or ever. But what I just did there is instructive. If I hadn’t turned around and told you my little story wasn’t true, you’d probably go on believing it. Maybe you’d even repeat it at some point.

This probably wouldn’t ruin your life. But what if the slightly-not-true story I told you was about something consequential?

What if you went on believing or repeating that false, but consequential idea, and it changed the way you made an important decision down the line?

Or what if you repeated the false idea over and over, and then one day someone called you out and embarrassed you? With your ego bruised and reputation at risk, at some point you might even feel pressure to defend what you'd been saying even though it wasn't true. Right?

Against all logic, you might even go out on the internet in search of support for this false idea. This would be human nature. But with enough pressure on you, you might go to some pretty serious lengths to "save face" because of that thing you took at "face value."

You can see what I’m getting at here.

If we're not careful, jumping the gun on what the facts are can:

- lead us to make bad decisions; and/or

- paint us into corners that can lead to needless chaos or suffering.

Here's an understatement that's important enough to state:

If we want to solve problems in innovative ways, we need to have an accurate view of the world. It's essential to know what’s fact, what’s story, and what’s conjecture.

And doing that means continually questioning the "face value" of things.

And that's actually quite hard.

What does skepticism mean?

I’m not the first person to come to this conclusion. The idea of Skepticism—or not believing things exactly as they’re presented to you—dates back at least to Plato and Socrates. (True story this time).

The Scientific Method itself is built around the idea of being skeptical: trying to disprove incorrect ideas about how the world works. And as I’m a fan of saying, innovation is about questioning assumptions and “rules” that aren’t rules.

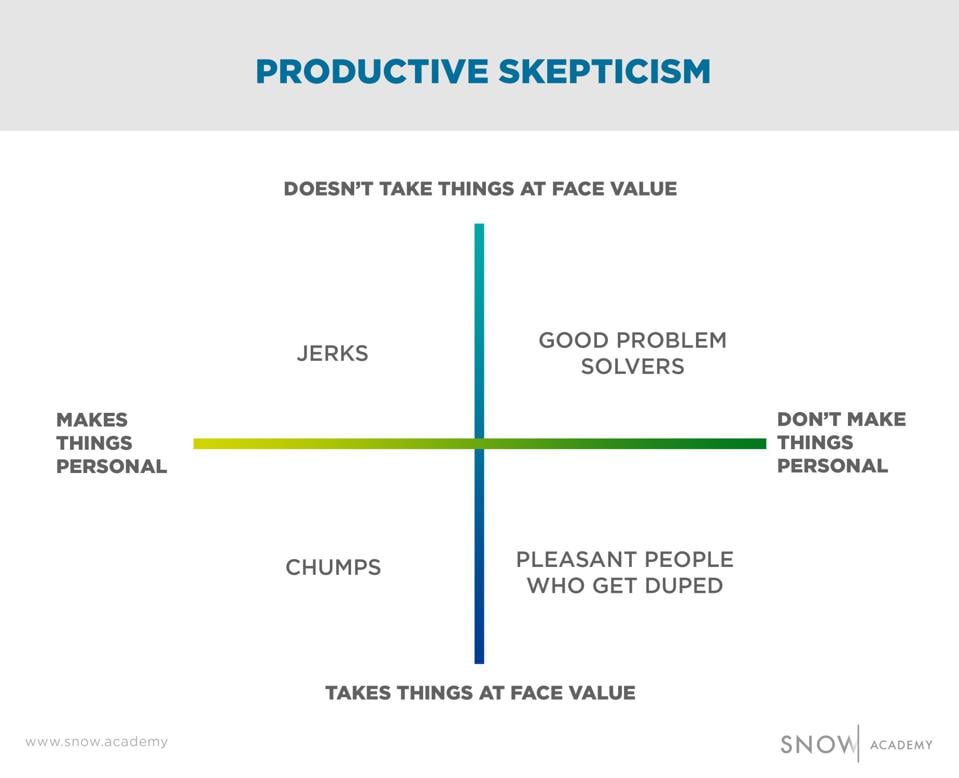

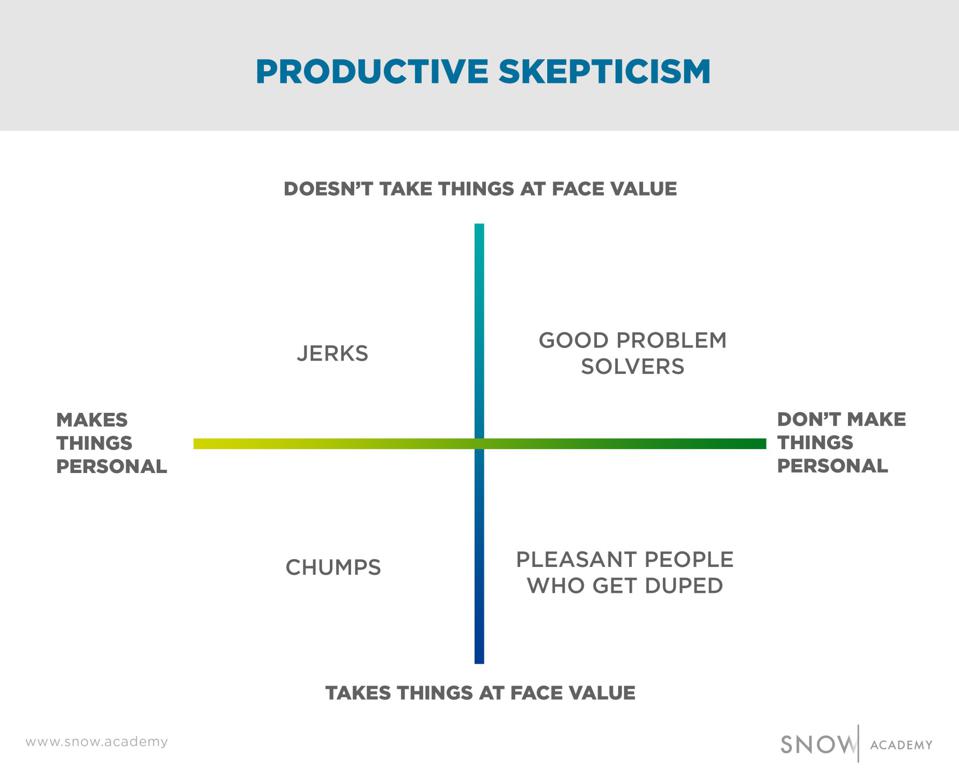

But one of the big problems with skepticism is it's often delivered in ways that don’t move the ball forward. The guy who interrupts the presentation to gleefully shoot a hole in it in front of everyone… is often not trying to be helpful. He's a jerk.

And because most of us don’t want to be like that guy, we often hold back when we have questions. We don't dig into the premise on which an ally's argument is being built in order to keep our alliance.

Even more than that, psychology research has long shown that humans simply default to believing that what’s being presented to us is true. When Bernie Madoff told very smart investors that the unbelievable returns of his investment fund were legitimate, they believed him. For decades, literally only one skeptic—Harry Markopolos—tried to sound an alarm that Madoff’s story shouldn’t be taken at “face value.” (Gladwell’s latest book Talking To Strangers does an elegant job of fleshing both this story and that phenomenon out.)

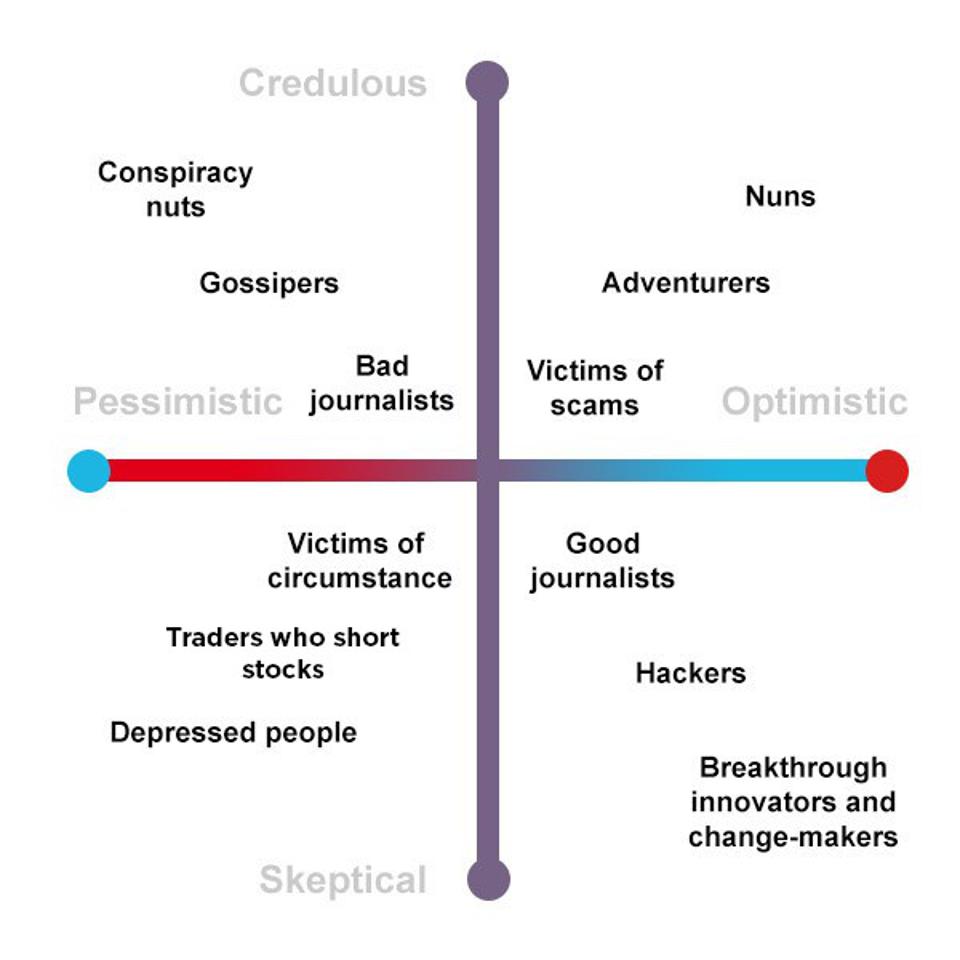

One of the biggest patterns I’ve observed in my work on innovation and teamwork is that innovative people tend to look at information that’s presented to them skeptically. They don’t believe what everyone tells them without checking it.

But they’re not doom-and-gloom pessimists either. The smartest ones question assumptions while believing the best is possible.

The most innovative leaders and problem-solvers, in other words, are Skeptical Optimists:

So how can we be a little better at the productive kind of skepticism? The kind that leads to good decisions and not being seen as a jerk? I want to share three principles:

Productive Skepticism Doesn’t Make Things Personal

One of the hallmarks of an intellectually humble person is the ability to detangle your identity from what you currently think. Psychologists call this "separating your ego from your intellect."

When people are too attached to their ideas, they feel under attack when people question them. After all, if you are your ideas, and your ideas turn out to be wrong, what does that say about you?

This leads even smartest and upstanding people to fall for intellectual dishonesty.

So the first key to expressing skepticism is to make sure that everyone knows you don’t mean anything personal—and that you're not going to take anything personally.

One of the easiest ways to do this is to literally tell them that. Spell out what you don’t want them to think. Some variation of this can go a long way:

“I have so much respect for you and how you think. So I don't want you take this personal. I'm just genuinely curious:

How do we know that's true?”

This plays into the philosophical principle of charity that I recently wrote about. Let people know that you assume the best in them. And then question them.

(Side tip: Don't use the phrase "with all due respect" if you want to sound genuine. It's used sarcastically so often that it won't.)

On the inverse, when we find ourselves on the receiving end of skepticism, the more we can take a breath and remind ourselves that we are not what we think or say, the better we’ll be able to not TAKE skepticism personally, too.

Productive Skepticism Looks Inward

It’s much easier to get into a habit of questioning things that are presented to us at “face value” by others than it is to apply similar skepticism to ourselves.

Yet, much of our basis for how we see the world and operate in it is built on things that we’ve already taken at face value. We navigate our lives based on a whole lot of assumptions.

And the longer we operate with assumptions, the harder it is to let go of them even when they turn out to be more consequential than a fun story about presidential faces.

If we want to be productive skeptics, we can’t discriminate. We need to develop the habit of looking at our own assumptions just as skeptically as we do other people’s.

To do this, I recommend a couple of simple (but not necessarily easy) practices:

First, whenever you find yourself conjuring up an argument, stop for a second and ask yourself two questions:

- Where did this come from? And

- Is it really true?

The first question is one of the most powerful you can get in the habit of asking. Identifying the source of our assumptions makes it easier to determine how worthwhile they are. And it also makes it easier to let go of them when you can tell yourself the story of how you came to hold them.

It's not part of you if you remember the story of how you got it.

The second habit is this: Whenever you notice yourself feeling strongly about something, use that as a trigger to stop and think. One of the paradoxes of human psychology is how incredibly important our feelings are… while simultaneously being very bad for decision-making.

Assuming that how we feel is an accurate representation of reality is one of the BIGGEST misplaced assumptions we make.

When you feel a strong emotion, that means that something is important to you. But it doesn’t mean that the emotion should replace logic. By using strong emotions as a trigger to stop and think—rather than using them as a trigger to act—we can short circuit a natural human tendency that gets so many of us in trouble.

So be grateful for your emotions. And then be skeptical of what they assume.

Productive Skepticism Doesn’t Stop

One of the areas of research I’ve been excited about over the last few years is the groundbreaking neuroscience of Oxytocin—and its relationship to empathy.

Popular TED talks and books (including one of my own) have explored how his little brain molecule helps humans build trust and empathy—and how great stories and acts of kindness cause our brains to synthesize it. One of the most powerful effects that neuroscientists have found is that learning another human being's personal story releases Oxytocin and helps make people from different groups more likely to care about each other.

After all of this exciting research, a couple of months ago a friend of mine burst my bubble. He told me that some researchers had debunked the assertion that Oxytocin builds empathy between people. They'd found that Oxytocin actually makes people double down on their “in-group” and act less kindly to people who are not like them!

Popular articles in major outlets made devastating hay of the news. Science journalists wagged their fingers at those of us who hadn’t looked at the Oxytocin research with enough skepticism.

But then came the twist.

A thorough analysis by a group respected scientists debunked the study that had supposedly debunked Oxytocin. It turns out that the guy who’d claimed to overturn the Oxytocin and empathy research did not just a shoddy job, but actually did a shady job. The experiment drugged people with an unnatural amount of Oxytocin and primed them to be empathetic to the experimenter, who then primed test subjects to share less money with people in their out-group. Far from proof that rigorous empathy research before was false, or that Oxytocin makes you hate people of other groups, it was like "inferring what dopamine does from giving people cocaine," as one scientist put it.

The irony is that all the reporters and bloggers who wrote about how we should have been more skeptical of the empathy studies… didn’t apply skepticism to the second set of research. After all was said and done, it was the skeptics who weren't consistent who got egg on their face.

Once again, productive skepticism doesn’t discriminate. It doesn’t stop at the point that it makes for a good blog post. I’m not saying you need to keep questioning everything in a rabbit hole forever. You have to move forward at some point with the best information you've got.

But what I’m saying is skepticism is only useful if you use it.

Being A Good Skeptic Takes Guts—To Explore And To Be Criticized

One of the things that’s tough about applying skepticism, is it’s often unpopular. It can look bad to question experts or authorities—or to slow things down with questions at all.

But then again, Sherlock Holmes didn't care if the detectives in Scotland Yard didn't like the questions he asked. He cared about getting to the facts.

So when I hear smart people express skepticism about popular ideas—say, when Elon Musk questions whether the ripple effects of global poverty and subsequent loss of life are worth the short-term life-saving Covid shutdown strategy—I like to pay attention to those skeptical arguments.

It's not productive to just get mad and stop listening.

But I also don’t just believe in simply adopting a contrarian point of view just because it comes from someone smart like Elon Musk. We ought to look at his ideas skeptically, too. For example, is his ripple-effect argument ignoring the long-term positive effects of a shutdown strategy?

That's a topic worth discussing rather than just getting angry about.

Looking at the world this way is hard. It’s not as efficient as going with the flow of popular opinion, or changing our minds just because an "authority" figure said we should. But being willing to grapple hard with ideas and change your mind when it's smart to is exactly what intellectual humility is about.

And that’s where breakthroughs come from.