6 min read

The Importance Of Being Charitable (Especially When Approaching Conflict)

![]() Shane Snow

Jan 10, 2023 4:58:58 PM

Shane Snow

Jan 10, 2023 4:58:58 PM

.jpeg)

explorations > Teamwork > Trust

I once tuned in to a virtual conference talk that left me deeply unsettled. But the lesson we can learn from it is powerful, so I'd like to share it with you:

The speaker at this was giving a presentation about his life’s work, which involved saving endangered animals’ lives. It was a good talk, and a fascinating subject.

A few minutes in, however, somebody in the accompanying chat room began getting upset. They expressed that they’d felt “triggered” by something the speaker had said.

The details don’t matter, but the phrasing was not a slur or anything that’s seen as generally offensive. It just was controversial and made this particular person upset.

The chat room soon devolved into an argument about the validity of what the speaker had said, versus the commenter’s right to be offended at it. And that turned into a debate about the speaker's identity and right to speak at the conference at all.

Some people ganged up on the commenter, calling the criticism unfair. Others defended the commenter’s right to express their truth. A few people chimed in patronizingly, offering deference to the commenter in a way that pissed them off.

So, patronized and dismissed, the commenter began making personal attacks. The moderator kept jumping in to smooth things over, but at this point, everyone in the chat room was wound up.

The speaker, meanwhile, had no idea that any of this was going on.

He continued his speech, but people were paying attention to the argument instead of him. I’m glad he didn’t see the chat thread while he was speaking. Can you imagine?

This situation is a rather extreme version of something that happens quite regularly in life—especially when we don't see eye to eye in our teams at work.

A difference in opinion derailed a conversation, and tore a group apart.

There are a few different conclusions one might arrive at after observing this kind of exchange:

-

Person A did something wrong, and Person B was right to speak up.

-

Person B was wrong to not give Person A benefit of doubt, and people were right to defend Person A.

-

Everybody was wrong here and needed to chill out.

Now, I know I didn’t tell you enough detail to make a confident judgment about this particular situation. But there are valid arguments for each of these assessments.

It’s important to speak up, even if we might be wrong. Speaking up pushes a group forward, if the group is willing to have a difficult conversation. It’s also important to give benefit of doubt, and to stand up for people who are being treated unfairly or cannot defend themselves. And it’s also important to not lose our cool when debating ideas. The moment a conversation gets personal is the moment it begins to lose the potential to go anywhere productive.

However, I think there’s something even more important to consider about a situation like this—something that I think can dramatically alter the way we deal with people and model productive communication.

And that thing is embodied in a fourth option for how one could judge the above scenario:

-

Everybody was doing their best. The group just didn’t have the right framework to handle things in a way that could lead to a satisfying outcome, given their differences.

Productive Teamwork Starts With Proactive Trust

Research and history have proven over and over again that for a group of people to work together and make forward progress, they need to have trust.

And not just trust in each other’s abilities, but trust in each other’s intentions.

You need to believe that the people you deal with have good in their hearts if you’re going to weather differences of perspective and opinion without things getting personal.

However, it can be hard for someone to “prove” to you that they have good intentions. Especially if you hardly know them. (Say, if they're an outside speaker here to teach you, or a new team member here to help. Or a stranger who you're having a potentially useful conversation with.)

So trust can often become a chicken-or-egg scenario.

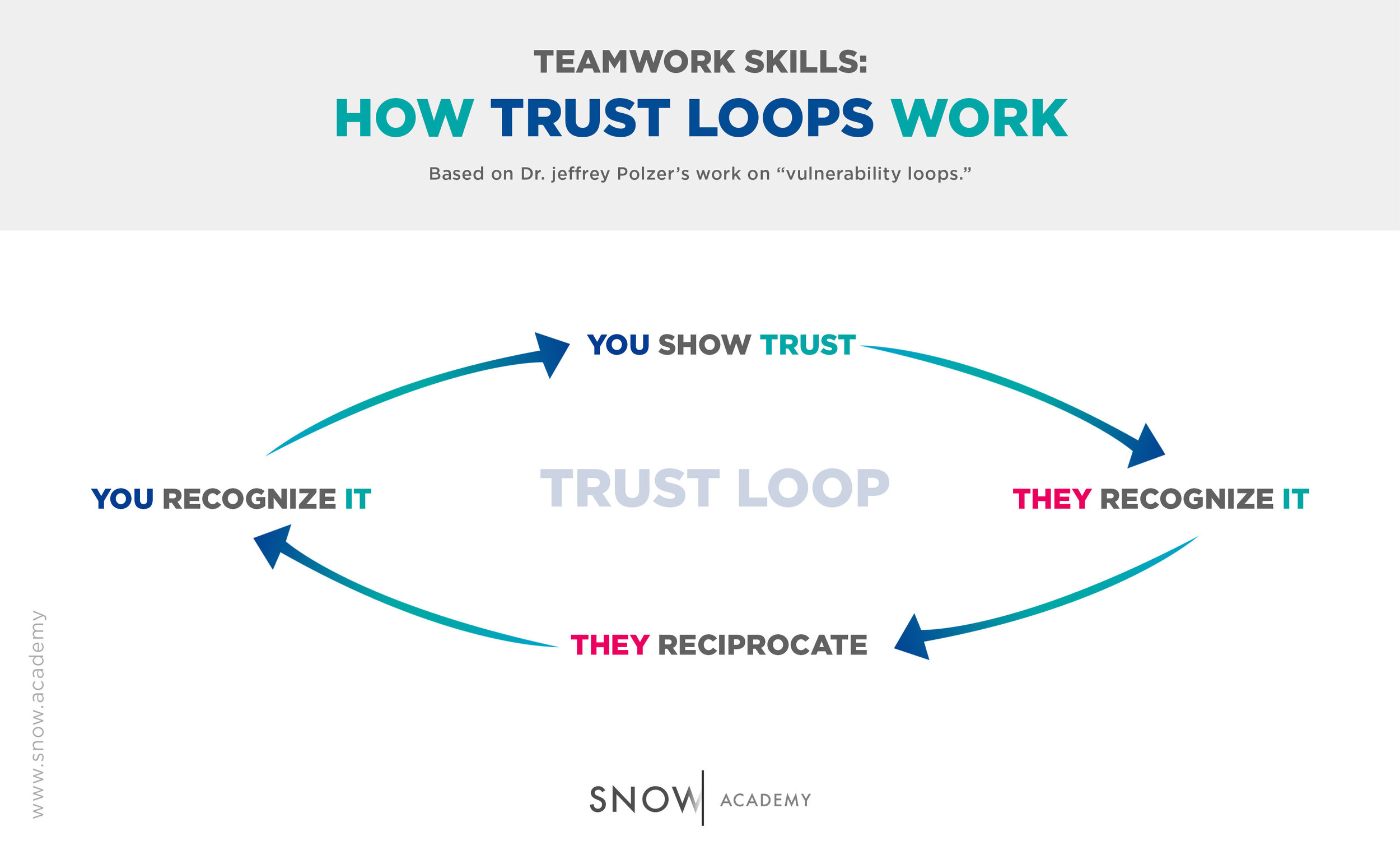

Psychology research tells us that showing people trust first is an incredibly effective way to have trust reciprocated on us. Harvard professor Jeffrey Polzer calls this process, a “vulnerability loop.” When you take a risk by trusting a person, that person is very likely to read that as a sign that they can show you trust.

In other words, when it comes to trust, the egg should come first—if you want to build it quickly, that is.

On the other hand, when trust has not been established, and somebody does something we perceive as wrong, it is hard to get a vulnerability loop going. When we perceive that someone is “bad,” we aren’t going to feel comfortable taking a risk on them.

This is where a wise person might recommend giving others benefit of the doubt.

Certainly, if the commenter in the story above had given the speaker benefit of doubt, that whole chat room mess could have been avoided. And if more people in the chat room had given the commenter benefit of doubt, the commenter would not have gotten even more upset.

But this is where a simple change in the way you frame things can make a powerful difference:

A Simple Change: From Giving Benefit-of-Doubt to Being Charitable

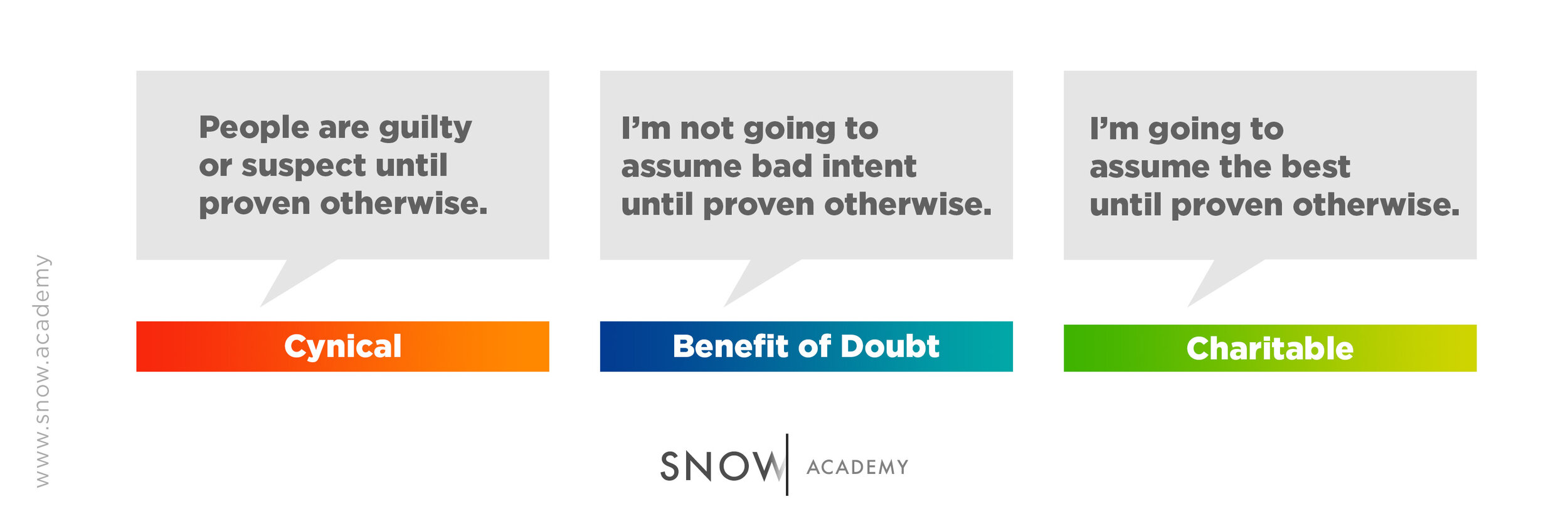

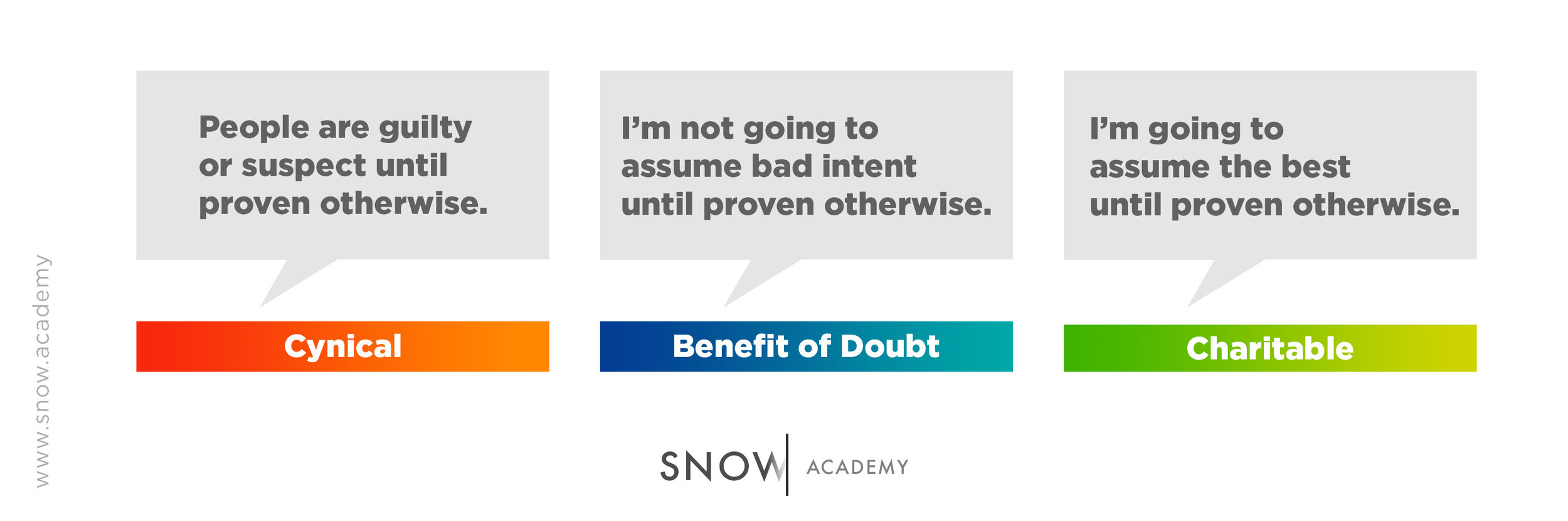

Offering someone benefit of doubt is deciding that you won’t assume the worst in them.

Treating someone charitably is deciding to assume the best in them.

This distinction is important. It’s the difference between action and inaction. Being charitable means seeking out the kindest explanations, and starting there when dealing with people—instead of sitting back neutrally and allowing people to prove themselves. (Or worse, treating people as if guilty until proven innocent.)

Here’s how that looks in action:

Let’s say that when the speaker at the conference had said the controversial thing, every person in the audience asked themselves a simple question before they reacted:

“What’s the most charitable way to interpret this situation?”

I’d dare say the answer in this particular case would have been this:

“This man has dedicated his life to saving animals. He’s here donating his time as a speaker to help people learn and to spread these noble ideas. I may not agree with his word choices or perspective on everything, but gosh darnit he means well.”

If the commenter who felt “triggered” by the controversial thing had thought the above before putting their fingers to the keyboard, they would likely have framed their comment more productively.

Note that I’m not saying that being charitable means we should keep our disagreement to ourselves. We often need people to speak up with their pushback, their questions, their different perspectives.

That’s how we get better together.

But if the person had spoken up from a starting place of being charitable, they might have framed their comment something like this:

“I believe this guy is doing good work and comes from a good place. But when he said X, I felt very uncomfortable. Can the moderator please ask him to clarify what he meant by this when it's an appropriate time for a question? I’d love to understand his perspective better.”

This would take courage for someone who felt upset to act with this kind of charity. And it would also create a much higher potential for a productive outcome.

Now let’s say instead that the commenter had reacted the way they actually did. In a moment of anger, they wrote, “Is anyone else hearing this? How dare he say X! I’m shocked that the conference would allow someone like this to speak.”

Let’s ask the other commenters the same question:

“What’s the most charitable way to interpret this situation?”

I’d dare say the answer might be, “This commenter cannot help but feel strongly about what’s being said. I may not relate to or agree with their reaction, but I believe they aren’t trying to be malicious. They are a good person and want to make sure that truth and integrity are upheld here, for everyone’s benefit.”

Imagine if that was how everyone in the chat thread interpreted the situation? I bet that the ensuring conversation would have been loaded with kindness and calm instead of patronizing or anger.

The result could have been a thoughtful Q&A with the speaker themselves. (It’s charitable to let someone respond to criticism themselves, after all!) And even if there was still disagreement in the end, at least a mutual understanding could have been achieved—instead of defensiveness all around.

Reacting Charitably Helps Even When Things Are Bad

To be clear, just because we show charity to others doesn’t mean that others will reciprocate it. Some people’s defensive walls take a long time to break down. Some people are quicker to trust than others.

And to be clear, just because we start from the most charitable explanations for people’s behavior, doesn’t mean that we’re always right about that. Some people do act out of malice, or bad intentions.

But most of the time, anyone who isn’t a psychopath does believe they are good deep down. So treating people as if they good intentions is much more likely to make even an unpleasant situation manageable.

Someone is much more likely to change their mind—and even admit they overreacted or were wrong—if you show them that you believe their heart is good.

tl/dr: assume the most “charitable” explanation for people’s behavior, and you’ll make more progress even if your assumption is too kind