7 min read

What Makes Good Storytelling, Based On The Paradox Of Sequels

![]() Shane Snow

Jan 15, 2023 12:17:33 PM

Shane Snow

Jan 15, 2023 12:17:33 PM

How important is originality in filmmaking? Instead of heading to the theater for Batman vs. Superman or My Big Fat Greek Wedding 2 last week, I took a painstaking look at the data on 600 recent movie sequels to find out. This is apparently how nerds spend their spare time. (My colleague Greta inadvertently joined the nerd ranks by spending her weekend helping me compile the data. Sorry, Greta, but also thanks!)

Though Hollywood’s first movie sequel, The Fall of a Nation, came out 100 years ago, studios have pumped out sequels in earnest ever since The Godfather Part II won Best Picture in 1974 and The Empire Strikes Back smashed box office records in 1980. In 2016, we’ve already had follow-ups like Zoolander 2, Ride Along 2, Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon 2, SLC Punk 2, IP Man 3, and Kung Fu Panda 3. By the time Bad Santa 2 premieres in November, theaters will have shown 35 major sequels just this year.

Interestingly, a quarter of the big sequels of 2016 are released over a decade after the first installments premiered. The number of these “late sequels” grows each year, hinting that movie studios are either hard up for original ideas or increasingly see sequels as good investments.

So how do you judge how good a sequel is? The most common stat cited for movie success is box office earnings, closely followed by critical reception and Academy Awards.

There are two big problems with using ticket sales as proxy for quality, though. First, as I pointed out in this recent data study on the Oscars, the films nominated for Best Picture by the Academy are never the highest earners. In fact, most winners don’t crack the top 50 in a given year.

But let’s put that aside for a moment.

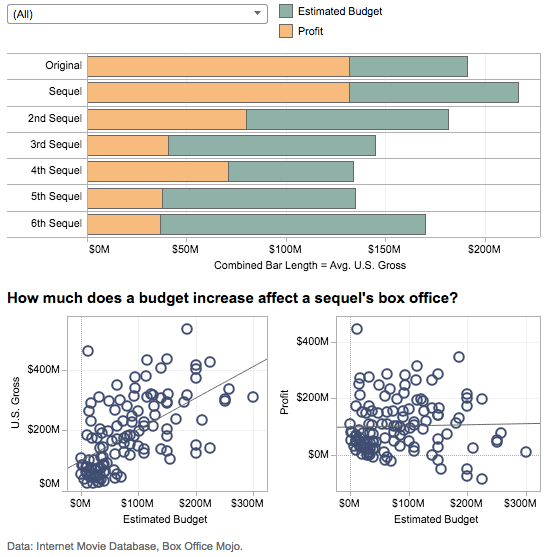

The bigger problem is that earnings are often a function of marketing. A larger budget — say, for a sequel to a film that earned a lot of money — may very well yield a big box office number. Spending more on big sequels is a rather safe bet. Here’s how the 34 most-popular, multi-sequel film franchises have performed in terms of profit versus budget:

This chart is courtesy of IMDB and Tableau. Play with the interactive version here.

Notice how despite bigger budgets (look at the data on sextologies!), the profits for sequels tend to continually fall. Even though spending more to promote a movie should make the movie more successful in theory, more budget spent on a sequel doesn’t correlate to more net profit.

Zooming out to the 600 sequels I catalogued (every sequel in the last 10 years, plus a few hundred sequels from previous decades, including less-popular franchises and those with just one sequel, like Nanny McPhee and The Expendables), the first sequel in a series grosses more money, on average, than the original — though as the above analysis shows, that doesn’t mean sequels have bigger profits.[footnote]In all these cases, I’m controlling for inflation.[/footnote] The second sequel of a franchise tends to make less money than the first sequel, and reboots, like 2009’s Star Trek, typically earn more money than their predecessors.

These, however, are averages, skewed by a few exceptional cases. When you look at the median picture, we find that typical sequels, including remakes, make less money in theaters than the originals.

It’s important to note that even though sequels usually make less money than their predecessors, they still make a lot more money than the average movie.

How does this work? If sequels are typically worse than their originals, why would sequels on a given year make more money than originals? The data actually tells the story quite nicely: Sequels only get made when the first movie is a huge success.

In reality, the view of the “average” movie earnings in a given year looks more like this:

While the chances of making a hit original movie are small — originals are either going to do really well, really poorly, or just okay — chances are good that a sequel based on an existing hit will beat the average.

In the business of movies, sequels are just safer bets.

However, as I mentioned before, dollars do not necessarily correlate to quality. Let’s take a look at how viewers feel about sequels after they’ve bought their movie ticket:

The story here is clear: We like sequels less than originals. We may pay to see sequels, but we don’t like a rehashed film as much as fresh one. (Side note: the entire plot of last year’s 22 Jump Street, the sequel to 21 Jump Street, is a self-referential allusion to the idea that a sequel has to just replicate the same story as the original. The repeat-the-original system of sequels has become so cemented in Hollywood that an entire film was extremely successful by poking fun at this idea.)

As we see from reviews and Academy Award nominations, many of the “best” movies are independent, low-budget, or small-distribution films. Sometimes the critical success of a small film after its theater run is over will lead to a big budget for a sequel, as was the case with The Boondock Saints:

The first Boondock Saints film made just over $30,000 — on a tiny budget. Only later did it become a cult favorite on DVD, which led to a sequel with a larger budget. A decade after the original was released, The Boondock Saints II: All Saints made $10 million. Here’s a sequel that earned over 22,000 percent more than its original when you adjust for inflation — which greatly skews our average. However, even though Boondock Saints II received favorable reviews overall, the audience liked it 20 percent less than the original, according to IMDB reviews data.

Not all sequels are good storytelling

Some categories of movie are more sequel-prone than others, and some — such as comedy and horror — tend to have worse sequels than the rest:

But what about the outliers? The sequels like Return of the King and Star Wars VII that blow us away as much or more than their originals? When you zoom in on the exceptions to our sequel median — both on the top and bottom — you’ll notice that sequels tend to fall into two distinct categories. The bottom-performing sequels are essentially repeats — similar plots, similar jokes, basically 90 minutes of nostalgia. But the top-performing sequels tend to continue and build on a strong story line. They’re not sequels; they’re sagas.

Here’s a breakdown of movie sequels by type: repeats, sagas, and reimaginations, which is when an older film gets a modern makeover:

Sagas fare about the same as their predecessors, while reboots get even more favorable reviews than the old version (although they earn less money; I theorize that this is because people tend to give reboots less of a shot in the first place after so many years).

A recent study on innovation by professors from the Universities of South Florida, Binghamton, Texas San Antonio, Munster, and Lausanne explains why we tend to like the continuing storylines of sagas better than repeats. The researchers concluded that people prefer ongoing storylines that mix both safety and excitement. In other words, we want novelty, but we need familiarity.

The best stories, according to the research, move forward with that dynamic over time. When things change too much, the audience revolts; but when things stay the same, the audience gets bored.

Most Sagas tend to have had a story developed (or at least thought through) before the first installment hits the silver screen. In fact, most Saga movie series are adapted from previously successful books or television shows. Here’s where the source material for movies in the last 20 years came from:

[footnote]Source: http://www.the-numbers.com/market/[/footnote]

Notice that adaptations from familiar material — comics, fairy tales, existing characters (spinoffs) — outperform original screenplays. (This data lumps repeat sequels in with original screenplays.) However, the majority of films and the bulk of the industry’s money are made from original material. The movie business is hungry for sure bets, but people are simply hungry for great stories, which keeps the industry investing in original screenplays in hopes of making the next surprise hit (and then hopefully generating many sequels from it). The trend clearly shows major studios cutting back on original screenplays and investing in sequels and adaptations. Interestingly, this is where indie studios may be able to seize opportunity and try more daring original films with the hopes of Internet buzz carrying them to big audiences. And between Netflix, Amazon, and Hulu originals and the trend in television series becoming as high production value as many films, I think we’re going to see a lot of interesting original movie bets placed in the future. That said, most of the movie marketing dollars still come from the big studios, which means the gap between sequels’ revenue and originals’ revenue — at the box office, at least — will likely widen.

Let’s discuss one last question: how do never-ending movie franchises like James Bond and Fast & The Furious (that are no longer based on a pre-written story or books) still manage to go on? Bond keeps its steez by rebooting with new actors and new paradigms every few movies, thereby bringing back the novelty factor to the series. Based on our data and the conclusions from the above study, it makes sense that each new Bond reboot will continue to do well with this strategy. And though Fast & The Furious started out on the same path as most Repeat-style sequel franchises, with two sequels that increasingly sucked, the series turned a corner when it brought the original cast back and turned the franchise into a Saga-style world, with interweaving storylines, complex characters with multi-movie development, and by gradually introducing new cast members to the ensemble. Basically, F&F managed to get back into the green zone of tension between familiarity and novelty. It managed to create something relatable and original.

Here Come The Sequels

This year is slated to launch the most big sequels ever, and double the number we saw as few years back as 2008. Why would that be, if sequels are usually such bummers?

The answer is likely twofold. First, when you look at the failure rate of movies in general, even though a sequel is likely to disappoint critically, it is also more likely to turn a profit for movie studios than a risky new idea.

Second, and perhaps most exciting for moviegoers, more and more sequels lately are of the Saga variety, which means we’re making stronger original movies that continue linear storylines rather than rehash the good ol’ times of previous films. Only two sequels have ever won Oscars for Best Picture — The Godfather Part II and Return of the King — and notably, both are Sagas.

Our most groundbreaking movies tend to be original. Gone With The Wind, Citizen Kane, Star Wars, Jurassic Park, Avatar. But if you’re making a movie, you may indeed be better off filming a Repeat reimagining a family or action movie from a generation ago, even if it means sinking a franchise into the mud. The paradox of the movie business is that while original movies change the game, safe bets pay the players.

Yet — as we see with Fast & The Furious, Skyfall, and the unexpectedly popular Mad Max: Fury Road, the sequel world is of exceptions to the data. Besides, categorizing movies is not entirely straightforward. What exactly is Batman vs. Superman? Is it a sequel? A reboot? A crossover? Whichever it is, I’m going to go ahead and call it horror.