.jpeg)

This treatise on productive brainstorming—or rather, alternatives to it—is based on dozens of scientific studies and voluminous research that went into my book Dream Teams. If you like it, please share and check out the book, or my posts on cognitive diversity and debate.

On May 25, 1787, a group of revolutionaries convened for a team writing project that would change the course of world history.

They dubbed their meeting the “Constitutional Convention of the United States of America.” And the way they conducted it still resonates for many of us working in today's companies.

Here’s what the official invitation to participate in the Convention read:

CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION:

Let us come up with a systemme of Government! Everyone powder your wigs and join us in the Continental Congress Room at 9AM sharpe, ready to brain-storm!

Remember:

No idea is a bad idea! We shall have free coffee and white-boards and bounce-y balls.

The Masons need the room after us, so we have a hard stop at 10. But don’t worry, we should be done by then!”

I’m being facetious here. But as far-fetched as the above sounds, how often do we take on important problems in business using an approach like the above?

All the time.

Groups of people have been coming up with ideas together since forever. Our ability to do this helped us take over planet Earth. And it certainly played a part in the real U.S. Constitutional Convention.

But the ritual of brainstorming—that thing we do when we gather around a table and throw out ideas to spark creativity and open up possibilities—has become one of the most popular problem-solving activities for teams today, despite its one big problem:

It doesn’t work.

At least not when we compare it to other things we could be doing.

Research proves this over and over again. To the point that the famous psychologist Adrian Furnham has said,

“Evidence from science suggests that business people must be insane to use brainstorming groups.”

Before you protest that brainstorming works for you, hang in here with me for a second. In this post we're going explore the challenges of brainstorming—and why what works for you may not really be “brainstorming” at all.

"Brainstorming" Comes From Advertising.

The term “brainstorm” itself comes from 1939. Alex Osborn, one of the partners at the ad agency BBDO, began holding “group-thinking” sessions to come up with ideas for advertising clients.

The goal of these sessions, he wrote, was to generate a large quantity of ideas by combining brainpower and withholding judgment. “The villainess is a gal called Prudence,” he quotes.

Ten years later, brainstorming and Osborn exploded in popularity with the publication of the book Your Creative Power. In it, Osborn defined brainstorming as “using the brain to storm a creative problem—and to do so in commando fashion, with each stormer attacking the same objective.”

In the book, he lays out the circumstances for such brainstorming to work:

-

How big of a group? “The ideal number is between 5 and 10,” Osborn writes.

-

What sex or sexes? “A group of men seems best,” Osborn declares.

-

What caliber of minds? “The ideal group should include both brass and rookies,” Osborn explains.

-

The best overall group? Naturally, Osborn explains that his people at BBDO are best at it. “I found it far tougher when I organized a volunteer group of the brightest young executives in our community."

Osborn’s book won BBDO a lot of business. And unfortunately, like that thing about your tongue having different spots to taste different flavors, Osborn’s assertion that brainstorming got canonized into textbooks and repeated throughout American culture until they were taken as granted—even though both have a common problem:

They’re wrong.

Research SHOWS that it's better to just brainstorm on your own.

The very first scientific test of Osborn’s brainstorming method happened at Yale in 1958. In the experiment, groups of students were given creative puzzles and instructed to follow Osborn’s rules of brainstorming:

-

Focus on a specific, single target.

-

Withhold criticism. No idea is a “bad” idea.

-

Go for volume of ideas.

-

The crazier the idea, the better. (“It’s easier to tone down than think up.”)

The results were a staggering refutation of Osborn’s premise. Solo students came up with twice as many solutions as the groups did. And a panel of judges rated the solo students’ ideas more “effective” and “feasible."

The group setting, in other words, suppressed creativity.

More studies have found the same thing over and over. The science can be summed up by Washington University psychologist Dr. Keith Sawyer: “Decades of research have consistently shown that brainstorming groups think of far fewer ideas than the same number of people who work alone and later pool their ideas.”

Why would this be? The answers have to do with social dynamics and personality diversity.

Subconsciously, members of a group will prioritize staying in good standing with their group over many other goals. People who feel more secure will be more vocal in expressing ideas that push the boundaries versus those whose acceptance feels more tenuous. The level of psychological safety in the group will be a constraint on the creativity of expression—and that will be a function of the people in the room.

Then there's personality. Introverts will be less likely to vocalize ideas in a group setting than in a smaller setting. Other personality traits will affect participation as well.

These are just a few of the more common psychological effects at work in a group setting. But the result of all these social dynamics is clear: the success of group "storms" is a roll of the dice.

Brainstorming Groups Are A Management Crutch

So why do we keep at the group brainstorming ritual despite the overwhelming evidence that it’s not the best way to unlock a group’s creativity?

I’d wager the answer is because it’s easy.

As a manager, if you want to involve your team in a problem-solving process, a brainstorming session is a relatively painless way to pull this off.

You don’t need to manage any conflict—no idea is a bad idea, after all!

You don’t need to explain yourself when you don’t implement your team’s ideas—you can’t implement a huge volume of ideas, after all!

As author Scott Berkun puts it, “The bad reason that brainstorming is popular is that it is a convenient way for bad managers to pretend that the team is involved in the direction of the project. A team leader can convince themselves that they know how to cultivate and work with ideas that are not their own simply by holding a meeting.”

It gets worse. The power dynamics of having a manager in the room during a brainstorm session takes even more away from the group’s creative potential.

As Stanford MBA school professors Jeffrey Pfeffer and Bob Sutton point out, “When a group does creative work, a large body of research shows that the more that authority figures hang around, the more questions they ask, and especially the more feedback they give their people, the less creative the work will be. Why? Because doing creative work entails constant setbacks and failure, and people want to succeed when the boss is watching–which means doing proven, less creative things that are sure to work.”

However, All This Brainstorming Research DOES Point Us To A Reliable Way To Unlock Group Potential

Whenever a new study shows yet again that group brainstorming doesn’t work well, business gurus and consultants erupt in protest. They’ll say that the studies were too narrow, that the experiments don’t run brainstorming sessions like they do. That you should hire them because, like Osborn argued, their way of doing this works better than if you do this on your own.

It turns out that we can overcome the problems with Osborn-style brainstorming. And we don’t need to hire those guys to do it. All the above research—and a little more—teach us how.

To do it, we need a structure to overcome the problems with brainstorming that we've outlined so far:

-

There’s huge variability in success based on how a brainstorm session is set up.

-

Group dynamics and power dynamics lead people to hold back.

-

A large quantity of ideas does not mean quality of ideas.

-

Brainstorm sessions often have little follow-through because the point is usually to involve the team rather than solve the problem. (Or because the problem doesn’t actually get solved through the brainstorm session.)

Any group discussion will live or die by its setup. Given the right instructions, the right group, and the right follow-up, even a creative group meeting can be productive.

"Effective brainstorming is not just sitting in a whiteboarded room and allowing the loudest person to pontificate,” says Allen Gannett, author of The Creative Curve. “Effective brainstorming is highly structured, collaborative, and driving towards a specific solution."

In this sense, Osborn taught some important caveats for making brainstorming more effective than an aimless discussion. Some of his rules have been solidly disproven. But guidelines like having “a single target” rather than a general topic do promote group creativity.

To maximize our chances of effective group problem-solving, we need to structure our efforts so that we minimize negative social dynamics and maximize the potential for quality ideas rather than sheer quantity. And we have to make sure that we’re tapping into our teams for more than symbolic participation.

Research shows us that some things can indeed lead brainstorming sessions to outperform a typical Osborn-style brainstorm. Things that improve outcomes include:

-

Having more cognitive diversity in the brainstorming group.

-

Injecting outlandish or extreme ideas, thereby pushing the boundaries of what’s “acceptable” or “safe” for participants to suggest.

-

Getting the group in a good mood at the beginning of the session.

-

Giving participants prompts designed to get people out of their normal mode of thought and kickstart lateral thinking, such as “what if we had to make this 10x better?”

-

Having participants do all of the above on their own time, thereby coming to the group discussion prepared.

-

And most of all: Actually debating whether ideas suggested are good or bad, rather than withholding judgment. (This is where the lifetime of research by Dr. Charlan Nemeth of Berkeley is particularly powerful: every study of brainstorming vs debate shows that debate wins.)

But a group leader who can lead a thoughtful, structured brainstorming session involving the kinds of techniques above can do even better by reframing brainstorming as something else...

What's Proven TO Be Far Better Than Brainstorming? Science!

Research has shown that The Brainstorming Method is variable and unreliable. It can lead you to creative ideas, but only if you’re both structured and lucky.

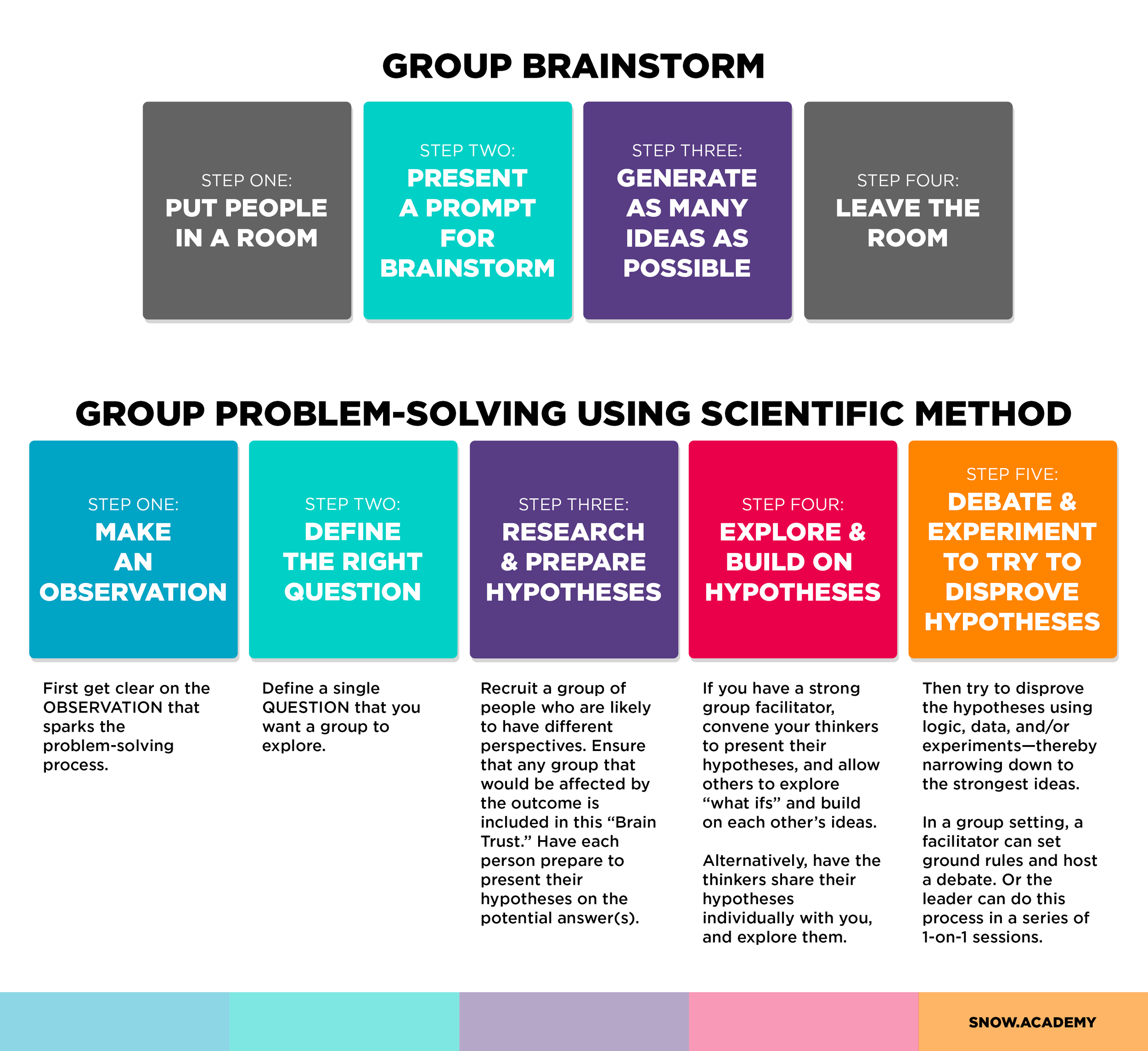

Fortunately, science has an alternative for creative problem-solving that’s completely reliable: The Scientific Method. When we map what we know about group dynamics and brainstorming to the steps of The Scientific Method, what emerges is an elegant, straightforward process.

The Scientific Method:

-

Make an observation

-

Ask a question based on that observation

-

Make a hypothesis about the answer to the question

-

Try to disprove the hypothesis

-

Analyze the results of your hypothesis-busting efforts

-

Repeat until you find the best answer

Applying the scientific method to group problem solving helps us immediately add structure to eliminate some of brainstorming’s most common problems.

OBSERVATION: First, we need to get clear on the thing this is about. What’s the Observation that’s kicked off this problem-solving exercise? E.g. Sales are down this quarter versus last year.

QUESTION: Once that’s clear, we can ask the Question, the thing we would normally get into a room to brainstorm. But by making the Observation clear first, we can make sure we ask the right Question. E.g. How can we improve sales year over year?

HYPOTHESIS: Now we need some hypotheses. This is where brainstorming would normally tell us to get a group of people around a whiteboard and throw out ideas. But when we frame things in terms of a Hypothesis, we’re required to do a little more prep-work, and a little harder thinking than usual. Which is a good thing.

“The biggest mistake people make when it comes to brainstorming is thinking that it means free-associating,” says Gannett (author of The Creative Curve).

Instead of throwing people in a room with sticky notes, “cast” a group of diverse thinkers who are likely to have different perspectives. Then give them a brief of the Observation and Question. Let them think up hypotheses on their own (and you can give them creativity-boosting prompts like the ones above if you want). And ask them to prepare to present, explore, and debate their and others’ hypotheses.

(Often managers will hold brainstorming meetings because they know their team members won’t take the time to come up with ideas on their own, so the meeting becomes a time block that forces people to participate. But if you can’t get people to do work on their own time, I’d suggest you have them block out time to do so on their own—and if they still won’t prepare for a meeting, then get rid of them.)

Once you’ve gathered Hypotheses, I suggest breaking Step 4 of the Scientific Method into two activities: Explore & Refine Hypotheses, and Debate & Disprove Hypotheses.

Depending on the personalities of the people involved, you may want to make this step a series of small group (or even 1-on-1) gatherings rather than a large group session where social and power dynamics will play out in ways that may reduce psychological safety.

EXPLORE & REFINE HYPOTHESES: Before you try to cull the bad ideas, take some time to build on people’s ideas. Suspend your disbelief, open your mind, and ask some what-ifs: “What if this were true?” or “What if we did do this?” etc.

If you do this as a team, then building on each other’s ideas becomes a shared goal, and you’ll be more likely come up with ideas that no one individual could have on their own.

DEBATE & DISPROVE HYPOTHESES: After you’ve generated hypotheses and built them up, you need to try to poke holes in them. This is where most brainstorming activities get demolished in experiments. Here it can be helpful to have people on each side of a debate. But if the group’s shared goal at this point becomes trying to disprove hypotheses, then it’s easier to keep the exercise from getting personal. The goal of The Scientific Method, after all, is to find the truth, not to be right.

(For a primer on hosting a productive debate, check out my HBR article on the subject. For in-depth debate skills and practice, check out the Dream Teams course on Snow Academy.)

EXPERIMENT: At a certain point, a good debate like this will end up where The Scientific Method often does: with the need to run a test.

This sets a group up for the perfect follow-up where brainstorming usually stops. The Hypothesis or Hypotheses that are most intriguing move on to become experiments.

ANALYZE: After running experiments, the group leader can analyze the results and see if they need to repeat the process.

The best Brainstorming is more like Sparring. Because Real Group Problem-Solving Requires Sparks.

Just because The Scientific Method is straightforward and proven doesn’t mean following it is easy. But that’s exactly why brainstorming is less effective—because it’s so easy.

Group creativity is born of the friction between our different ways of thinking.

I’ve realized recently that one of my go-to methods for coming up with creative ideas—ways to solve problems, improve things I’m writing, etc.—has been to workshop ideas with people who really push my thinking. It turns out that, by some people’s definition, I like to engage in a bit of “brainstorming” after all. But what I’m doing isn’t Alex Osborn’s definition of brainstorming. It’s an informal version of the EXPLORE and DISPROVE stage of the Scientific Method.

And it’s often painful. I’ll excitedly present my wife (and business partner) with my solution to a problem we’re working on, and she’ll ask a single question that refutes the whole thing—but this question will lead me to a much more interesting solution. Or I’ll show up to the bar armed with what I think is a great idea, only to have my director buddy Brandon shoot holes in it… and help me find a tangential idea that’s even stronger.

Few great innovations in history came from a traditional brainstorm session. Especially compared to the amount of innovation that's come from groups of people having extended periods of cross-pollination and debate.

After all, the actual U.S. Constitutional Convention lasted nearly five months. It consisted of hundreds of debates, and thousands of hours of prep-work behind the scenes.

And the output was a solution so clever that it became a new “best practice” for the whole world. One that has held up for a remarkably long time.